I usually don’t review books on this blog. But sometimes I come across books that deeply move me and that I want to share.

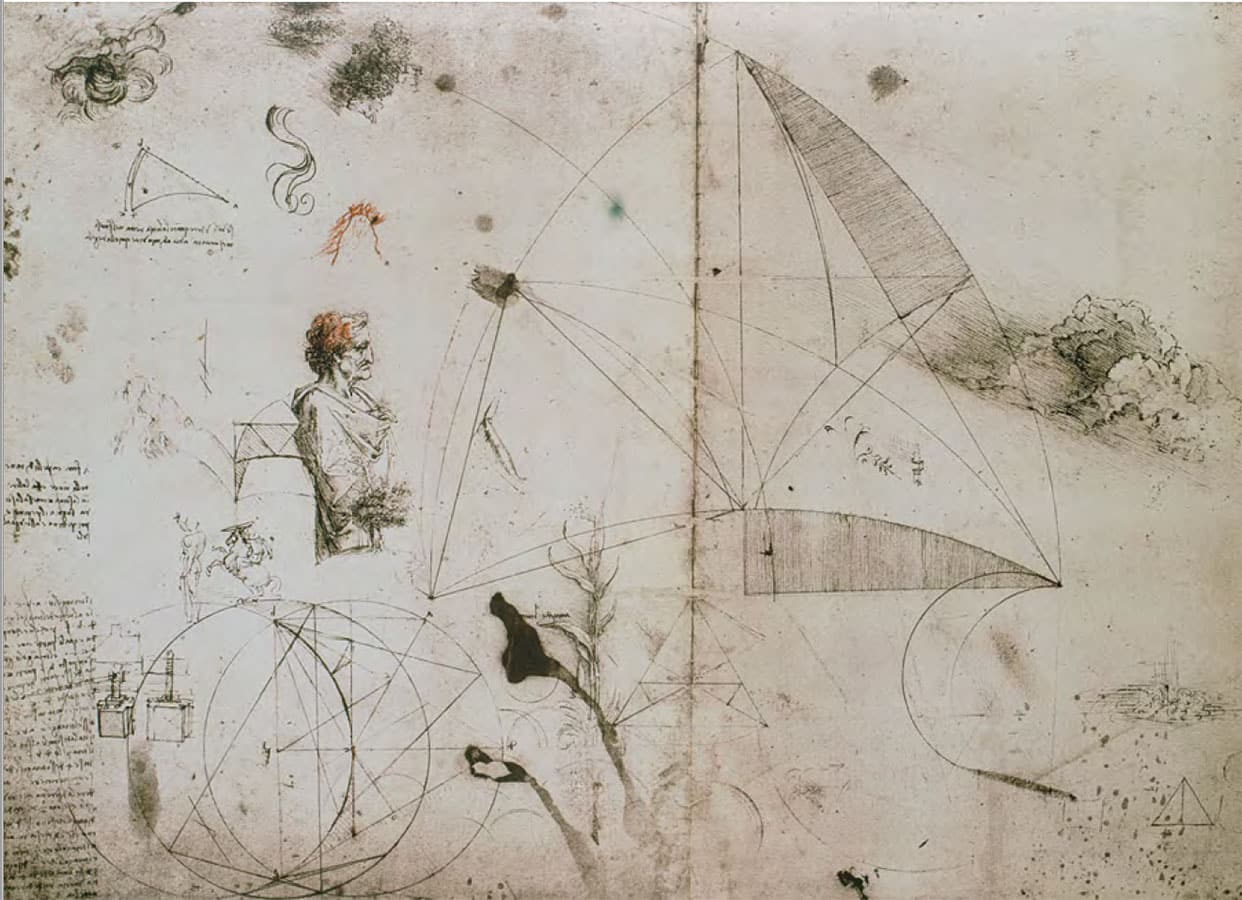

The biography of Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson is a book that not only tells you more about an artist’s life and work, but also is a powerful example of how an artist makes use of his sketchbook for his entire life.

The book takes you deep into da Vinci’s life, or at least what we know about it, because as we learn, a lot about Leonardo’s life lies in mystery. Not surprising because the man has been dead for 500 years (literally 500 years in 2019 – if you’re in Europe, then keep your eyes open for special exhibitions this year!), and then again a bit surprising because he kept detailed notebooks for his entire adult life.

So we all know that Leonardo da Vinci was a polymath, and a genius of his time – and had he lived in our time, one wonders what he would have achieved.

He made anatomical, architectural, nature and engineering studies. He dissected the human body (as well as many animal carcasses) and studied it in detail unlike anyone before him. Some of his concepts for flying machines, although they never left the drawing board, have proven to be working. And he was also quite the masterly painter – this becomes almost an afterthought when you consider all his other interests and vocations. Leonardo seems to have thought the same, Isaacson writes: “When he reached that unnerving milestone of turning 30, he writes a job application to the Duke of Milan and he lists all the things he can do in 11 paragraphs. And the first 10 paragraphs are sort of engineering and design, like, I can design public buildings, I can divert the course of waters, I can make weapons of war. It’s only in the 11th paragraph where he says, I can also paint.“

Here is a human who loved to study everything around him – particularly nature – he loved to draw water and spiral forms like hair (take a look at the curls in his portraits!). He took extensive notes about everything that interested him – and so his biggest legacy to us are his more than 7000 notebook pages, that show his deep curiosity and eagerness to find out new things about the world, celebrate their beauty and find out how stuff works.

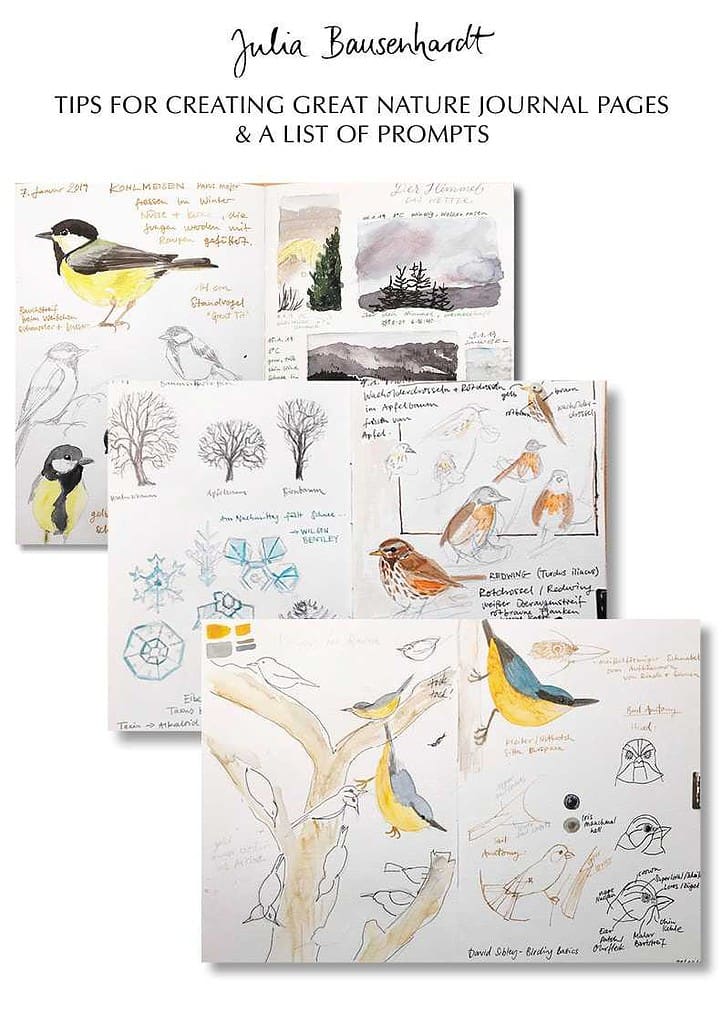

And this is where our sketchbook drawing habit comes in. In fact, Leonardo could be described as the godfather of nature journaling.

One of his notebook entries goes like this: “Describe the tongue of a woodpecker.” And in fact, when we research this, this little bird’s tongue is quite peculiar. The European woodpecker’s tongue is very long, so that the bird can capture insects with it, and the tongue curls back around the skull to protect the bone while the bird is drilling and pecking into wood. Quite ingenious.

Master Leonardo is looking for these cool things in nature everywhere. He’s simply interested in it all and marvels about everything. So much that he, as Isaacson writes, rarely finishes anything. He keeps paintings around for years, making almost indistinguishable changes to them while he’s traveling around (La Gioconda, better known as the Mona Lisa being one of them). He fails to finish work for his patrons (which, from a freelancer’s perspective nowadays would be considered career suicide) or uses highly unusual techniques (the painting layers of The Last Supper came off after a few years because da Vinci used an experimental fresco technique based on oil, which didn’t stick to the wall). His anatomical studies of the human body could have been a milestone in medical knowledge, because he was far ahead of his time – if only he had organized and published them. In a way, I can understand how he must have felt, because on an ordinary day, I have 20 different unfinished projects floating around in my head, screaming for attention.

But instead of finishing, Master Leonardo’s attention always turned to the next thing, and this could be a measurement of the sun, or a church design, or why the sky is blue, or squaring the circle, how a bird can fly (he figured it out), or the way a dragonfly’s wings flap. And of course he made his wonderful sketches right next to his thoughts – his words always in mirror writing, and his sketches always with the characteristic upwards hatching, because he was left-handed. And he just filled page after page like this.

Isaacson writes: „Leonardo was curious to know everything there was to know about everything you could know about creation, including how we fit into it.“ And maybe it’s his way to fuse science with art that’s so fascinating – connecting everything across disciplines. He loved to experiment, and understood nature by observing the patterns in it, not by thinking about theoretical concepts. And it’s this power of observation you can see everywhere in his notebooks.

Isaacson writes: “These are things we could all do if we would pause a few times a day, maybe even a few times an hour and say, ‘Let me look a little bit more closely at that.’ And by doing so, we would see how things cross different disciplines in nature and form certain beautiful patterns.”

This is the habit of nature journaling spelled out right there. This is why we should keep investigating and sketching what’s around us.

Sometimes a book can feel like it’s making a direct connection to another human being, like you can actually look into their head and see how and what they are thinking. So this book feels extremely close in some places, even though da Vinci has been dead for 500 years, and we will never really know who and how he was. It’s all just an approximation. But it’s one that has profoundly moved me. I know in part this is because I’m really interested in artists and their lives, and I’ve always liked to read biographies.

But even if you don’t experience these weird connections with dead artist’s souls, Leonardo da Vinci was an extraordinary human, with an undying curiosity and huge sensitivity to all living things, with a love to explore and investigate all of nature and its inner workings, and at the same time he struggled like all of us. I really recommend this book to everyone. Not just artists or those interested in nature or sketching, but everyone.

I love Leonardo too. I am fascinated by many artists and writers who have lived in different times. I love the fact that he kept a sketchbook and was so curious he didn’t finish things. So different in today’s world where we are expected to do one thing and are considered flighty and unserious if we have too many interests.